This story was originally published on May 11, 2017.

Justin Hill, 36, grew up in Convict Hill. He remembers the Southwest Austin neighborhood, which is part of Oak Hill, as a mix of rural and suburban – lots of cedar, oaks and rocks. His house butted up against a cliff, which descended into thick woods, where he and his younger brother would spend hours after school or on the weekends exploring.

Their active imaginations often seized on the history of the area.

“As a kid, my brother and I would just venture out there and play and take our BB guns out and pretend we’re explorers,” he said. “Once we found what we thought were gravesites, we definitely knew that would be a place we would try to find again.”

Hill and his brother aren’t the only ones who questioned the name and history of the subdivision. Southwest Austinite Valerie Nelson asked the question for our ATXplained series: "What are the origins of Convict Hill? Were there convicts there?"

Cheap labor

In 1881, the first Texas state Capitol building burned to the ground, and leaders set about building a new one. They wanted to use local materials, including limestone from a quarry in Oatmanville – the area now known as Oak Hill – so they built a 6-mile railroad line from Oatmanville to the Capitol site.

Then they needed workers.

“To keep the project as cheap as possible, and one would assume so other people could put more money in their pockets, they decided to use convict labor to do the work,” said Penny Levers, co-editor of the Oak Hill Gazette, which covers Convict Hill.

Rather than pay the going rate of 17 cents an hour, the state could lease prisoners out to contractors and pay them nothing. Most of these convicts were Black.

“Convict leasing began almost immediately in the aftermath of the Civil War, right in the shadow of emancipation and the end of the Confederacy,” said Robert Chase, assistant professor of history at Stony Brook University in New York. “What Texas and many other Southern states wanted to do was to enact some kind of law that would re-instill ‘order’ and really ‘racial order’ and racial oppression.”

Restrictions such as vagrancy laws, which effectively criminalized loitering and unemployment, ensured that recently freed people were often jailed – and forced to work.

And some of these workers were very young.

A collection at the Texas State Library and Archives Commission includes a roster of convict laborers from this period. One boy, named L.S. Beauregard, weighing only 90 pounds, is described this way: “Negro. [R]aised in Walker Co. Bad boy—several times punished. He is recorded 12 years old. I do not think him much more than 10.”

In 1886, those overseeing the Capitol building realized limestone was too soft to be the exterior of the building, and the bulk of operations moved to Burnet County, where convict laborers began mining the pink granite that serves as the exterior of the Capitol today. Years later, the quarry at Oatmanville didn’t yield much else, but the use of convict labor gave the area a reputation, the Austin American-Statesman’s Eudora Garrett wrote in 1928.

“It was during those years that one of the hills from which the limestone was being taken was given a name – one that signified tragedy and death – ‘Convict Hill.’”

Did anyone die on Convict Hill?

Convicts who were forced to labor for the new Capitol faced horrendous conditions – sweltering heat, little food and no medical care. According to an article from the American Statesman’s Betty McNabb, convicts subsisted on “a diet of cornbread and salt pork and coffee.”

“Living on the hill was not much better than dying,” she wrote in 1972.

LaToya Devezin, who worked as an archivist with the Austin History Center before becoming a university professor, says the conditions were horrible.

“You wake up – sun up to sundown – pretty much you’re cutting limestone for the Capitol construction,” Devezin said. “We don’t have an exact number here, but you do have people dying doing this work.”

Legend has it that up to eight convicts died, either because of poor conditions or because they were shot during escape attempts. They were buried on the hill. People like Chris Hill, Justin’s dad, believe it.

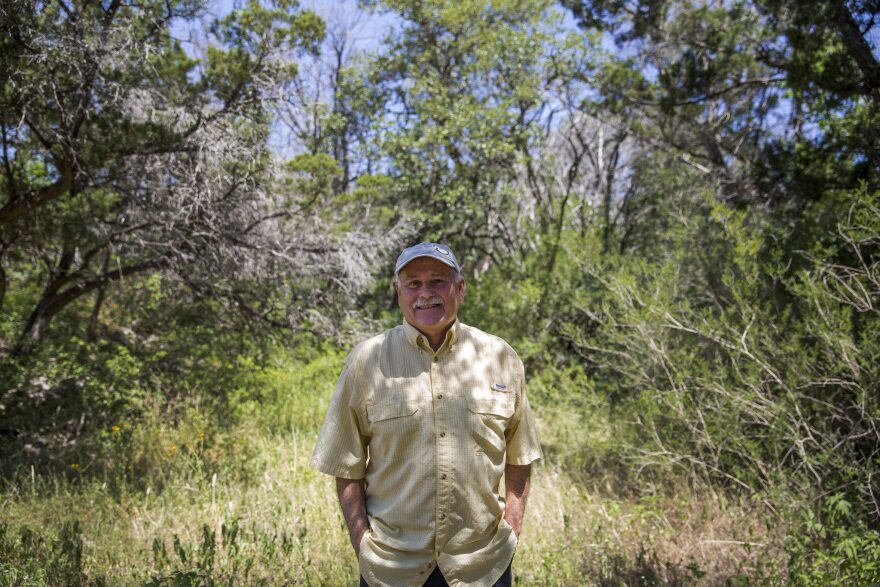

“Are there people buried out there?” said Hill, who said he saw cairns in the area, or mounds of rocks stacked upon one another to represent burial sites. “I don’t doubt it. Not one bit.”

Hill was the vice president of the Convict Hill Neighborhood Association back in the 1980s. He was also the area’s mail carrier for 30 years. When a developer bought land in Convict Hill and wanted to build multifamily housing – a stark difference from the small family homes in the area at the time – Hill and his neighbors brainstormed ways to stop the development.

“We kind of leaned back on the history of Convict Hill,” Hill said. “But we had to do a lot of homework.”

Neighbors read up in order to become local historians on the area. To block the development, the City of Austin wanted definitive proof that men had been buried on Convict Hill.

The neighbors didn’t have the resources for that. But the developer, Nash Phillips/Copus, did. According to a 1985 article published in the Austin American-Statesman, the developer hired an archeological firm to study the area. They were looking for high levels of phosphate, which might indicate human remains in the area.

In addition, according to reporter Monica Leo, investigators scoured the historical record for proof of a burial.

"[They] studied previous geological surveys, Capitol Commissioner reports, land grants, newspaper reports, deed records, prison reports, photographs and history books," she wrote. "They also interviewed a descendant of the original landowner.

But their results were inconclusive. No high levels of phosphate; nothing definitive in the historical documents.

Hill remains convinced that these men were buried where they may have died: on the hill.

“I can’t prove it,” he said. “But that doesn’t make it not so.”

But wasn’t living on the hill bad enough?

“Just the toil of their lives. And they were chained, balls and chains. They lived a very hard couple of years up here,” Hill said. “Their spirits [are] here. There’s no doubt.”

A deadman is buried

There’s at least one way to explain why the legend of the convict burials persists in Convict Hill: a deadman is buried there.

“What I know to be a deadman is a form of perpendicular reinforcement in a retaining wall,” said Travis Riggs, who works for Austin Masonry Construction in Arlington, Texas.

A deadman is often a log or concrete block buried deep into the earth, and it serves as the anchor for a wall meant to keep surrounding dirt or rock from falling into the hole that’s being dug. A retainer wall, and thereby a deadman, would have been used in a quarry like the one that was mined in Convict Hill.

“That deadman is holding the wall back,” Riggs said. And its name came about pretty naturally: “It’s submerged. It’s buried. You can’t see it.”