From Texas Standard.

In the present moment, all eyes are on the separation of families at the U.S.-Mexican border. However, Vance Blackfox can’t help but look back and remember the separations of his people in years past.

Blackfox is on the board of directors for the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition. He’s also Communications Director for Native Americans in Philanthropy.

The recently amended “zero tolerance” policy regarding immigration on the southern border has drawn comparisons to Japanese internment camps in World War II. But Blackfox is reminded of another injustice which he says is largely omitted from history lessons.

He gives workshops and holds conversations with community members about American Indians, Alaskan natives and their history. It’s a rare occasion when someone raises their hand because they’ve heard of the boarding school era.

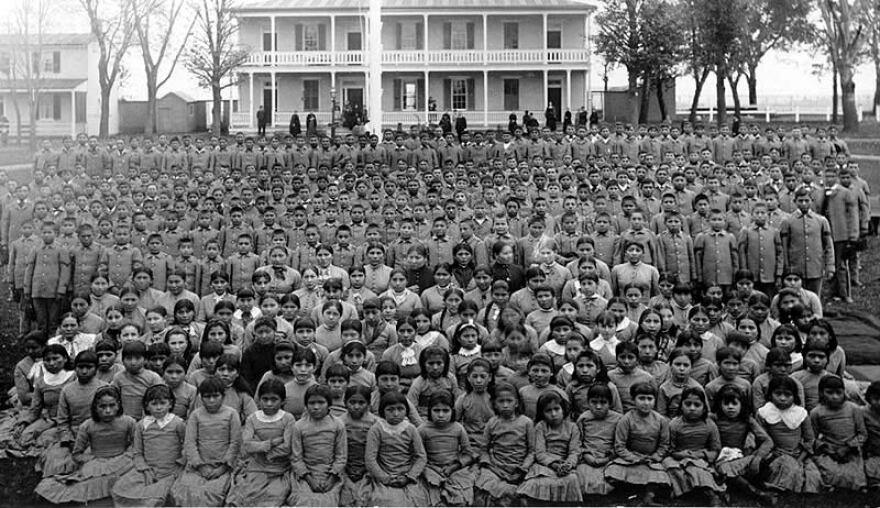

“Around the 1850’s and ‘60’s, the theme became for that century ‘Kill the Indian. Save the man,’ and the way in which they wanted to do that was to separate children from their home communities, from their parents, their families and put them into boarding schools,” Blackfox says.

Over 350 boarding schools were established by the federal government and either by voluntary admittance, coercion, or force, thousands of Native American children were enrolled. The government established “Indian Agents,” who conducted child round ups and raids.

And though some graduates of the boarding schools said “I wouldn’t be who I am today without it,” for many, the schools were a traumatic experience.

“More often than not, there are stories of molestation, rape, torture, brutal punishments and the like. They would come out these experiences really traumatized,” Blackfox says. “So traumatized that they were having to deal with addiction and not able to really host a family themselves and be a part of a family.”

It’s hard to know just how many children experienced the boarding school phenomenon of the 19th and 20th centuries because there was no system in place to account for them and many disappeared.

None of the boarding schools were in Texas. That’s because the majority of Native Americans in the state were either killed or sent to Oklahoma following the Battle of the Alamo. But that doesn’t mean this legacy of separation doesn’t live on here.

“My grandmother and my aunties were taken to boarding schools. Some of my uncles too and so most of us can say that that’s the case for our families,” says Blackfox.

So now, with Central and South American children held in detainment camps as their parents await processing and/or prosecution, Blackfox and his family can’t help but feel outraged by the shared experience.

“I think about what so many generations of native people on this land, brown people, being forcibly removed from their parents for years,” he says. “And it makes me angry and it makes me sad. Because I know, we know, that these children being separated from their parents are going to experience that same trauma and the same pain that so many of us have experienced all these generations since the boarding school era. Native people are so angered because we also know that brown people from Mexico and Central America who are coming here out of need and out of survival most of the time are also indigenous peoples. They may not know exactly their tribe or their affiliation but they are brown because they come from indigenous heritage. So once again, it’s happening.”

Written by Sarah Yoakley.